Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries Richmond VA

Office Location

Dr. Kiritsis' Specialties

Call Dr. Kiritsis to Schedule an Appointment

ACL Tears & Injuries

Disorders of the Knee | ACL | Sports Medicine

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is the most commonly injured ligament of the knee. In most cases, the ligament is injured by people participating in athletic activity.

As sports have become an increasingly important part of day-to-day life over the past few decades, the number of ACL injuries has steadily increased.

This injury has received a great deal of attention from orthopedic surgeons over the past 15 years, and very successful operations to reconstruct the torn ACL have been invented.

This guide will help you understand

- Where in the knee the ACL is located

- How an ACL injury occurs

- How doctors treat the condition

Anatomy

Where is the ACL, and what does it do?

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect the ends of bones together.

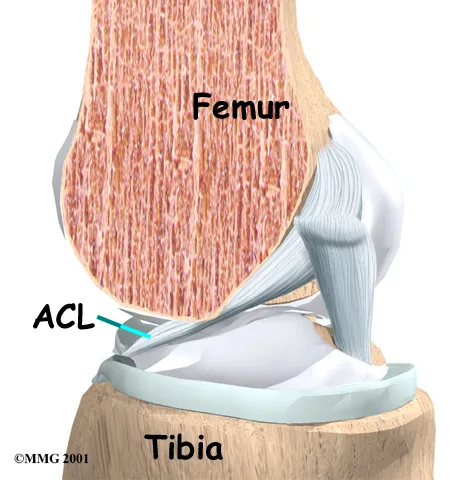

The ACL is located in the center of the knee joint where it runs from the backside of the femur (thighbone) to connect to the front of the tibia (shinbone).

The ACL runs through a special notch in the femur called the intercondylar notch and attaches to a special area of the tibia called the tibial spine.

The ACL is the main controller of how far forward the tibia moves under the femur.

This is called anterior translation of the tibia. If the tibia moves too far, the ACL can rupture.

The ACL is also the first ligament that becomes tight when the knee is straightened. If the knee is forced past this point or hyperextended, the ACL can also be torn.

The ACL also plays an important role in resisting the rotation of the tibia.

Other parts of the knee may be injured when the knee is twisted violently, as in a clipping injury in football.

It is not uncommon to also see a tear of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) on the inside edge of the knee, and the lateral meniscus, which is the U-shaped cushion between the outer half of the tibia and femur.

Causes of an ACL Injury

How do ACL injuries or tears occur?

The mechanism of injury for many ACL ruptures is a sudden deceleration (slowing down or stopping), hyperextension, or pivoting in place. Sports-related injuries are the most common.

The types of sports that have been associated with ACL tears are numerous. Those sports requiring the foot to be planted and the body to change direction rapidly (such as basketball) carry a high incidence of injury.

In this way, most ACL injuries are considered noncontact. However, contact-related injuries can result in ACL tears. For example, a blow to the outside of the knee when the foot is planted is the most likely contact-related injury.

Football is also frequently the source of an ACL tear. Football combines the activity of planting the foot and rapidly changing direction and the threat of bodily contact.

Downhill skiing is another frequent source of injury, especially since the introduction of ski boots that come higher up the calf. These boots move the impact of a fall to the knee rather than the ankle or lower leg.

An ACL injury usually occurs when the knee is forcefully twisted or hyperextended while the foot remains in contact with the ground. Many patients recall hearing a loud pop when the ligament is torn, and they feel the knee give way.

The number of women suffering ACL tears has dramatically increased. This is due in part to the rise in women’s athletics. But studies have shown that female athletes are two to four times more likely to suffer ACL tears than male athletes in the same sports.

Recent research has shown several factors that contribute to women’s higher risk of ACL tears. Women athletes seem less able to tighten their thigh muscles to the same degree as men.

This means women don’t get their knees to hold as steady, which may give them less knee protection during heavy physical activity. Also, tests show that women’s quadriceps and hamstring muscles work differently than men’s.

Women’s quadriceps muscles (on the front of the thigh) work extra hard during knee-bending activities and their quadricep-to-hamstring strength ratio shows their quadriceps are typically much stronger than their hamstring. This pulls the tibia forward, placing the ACL at risk for a tear.

Meanwhile, women’s hamstring muscles (on the back of the thigh) respond more slowly than in men’s. The hamstring muscles normally protect the tibia from sliding too far forward. Women’s sluggish hamstring response may allow the tibia to slip forward, straining the ACL.

Other studies suggest that women’s ACLs may be weakened by the effects of the female hormone estrogen. Taken together, these factors may explain why female athletes have a higher risk of ACL tears.

Symptoms of a Torn ACL

What does a torn ACL feel like?

The symptoms following a tear of the ACL can vary. Some patients report hearing and/or feeling a pop. Usually, the knee joint swells within a short time following the injury.

This is due to bleeding into the knee joint from torn blood vessels in the damaged ligament. The instability caused by the torn ligament leads to a feeling of insecurity and gives way to the knee, especially when trying to change direction.

The knee may feel like it wants to slip backward and there may be activity-related pain and/or swelling. Walking downhill or on ice is especially difficult and you may have trouble coming to a quick stop.

The pain and swelling from the initial injury will usually be gone after two to four weeks, but the knee may still feel unstable. The symptom of instability and the inability to trust the knee for support are what require treatment.

Also important in the decision about treatment is the growing realization by orthopedic surgeons that long-term instability leads to early arthritis of the knee and a very high chance of meniscal tears.

Diagnosis of ACL Tear/Injury

How do doctors identify ACL injuries?

The history and physical examination are probably the most important ways to diagnose a ruptured or deficient ACL. In acute (sudden) injury, swelling is a good indicator.

A good rule of thumb that orthopedic surgeons use is that any tense swelling that occurs within two hours of a knee injury usually represents blood in the joint, or a hemarthrosis. If the swelling occurs the next day, the fluid is probably from the inflammatory response.

Placing a needle in the swollen joint and aspirating (or draining as much fluid as possible) may be an option for pain relief and reduction of the swelling. If blood is found when draining the knee, there is about a 70 percent chance it represents a torn ACL.

This type of fluid can also be present if the cartilage on the surface of the knee joint was injured. Aspirating the knee is optional and is usually reserved for knees with significant swelling.

During the physical examination, special stress tests are performed on the knee. Three of the most commonly used tests are the Lachman test, the pivot-shift test, and the anterior drawer test.

The doctor will place your knee and leg in various positions and then apply a load or force to the joint. Any excess motion or unexpected movement of the tibia relative to the femur may be a sign of ligament damage and insufficiency. These exam findings are very good at predicting an ACL injury.

Another way to check for anterior tibial translation is with the KT-1000 and KT-2000 arthrometers. The patient’s leg is bent and supported on a wedge with the knee in 30 degrees of flexion.

The arthrometer is placed against the knee to be tested and strapped to the lower leg. Usually, the normal knee is tested first. The arthrometer applies an anterior force of 15 pounds against the tibia. The amount of anterior tibial translation is measured. The test is repeated with a force of 20 pounds.

A third test applies a manual maximal force to the posterior (back) of the tibia. This is similar to the Lachman test.

The results of these tests will help your doctor determine how badly the ACL was injured. Other tests may be combined with tests of ACL integrity to determine whether other knee ligaments, joint capsules, or joint cartilage have also been injured.

X-rays of the knee are very important and are used to rule out a fracture. Ligaments and tendons do not show up on X-rays, but bleeding into the joint can result from a fracture of the knee joint, or when portions of the joint surface are chipped off.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is probably the most accurate test for diagnosing a torn ACL without actually looking into the knee.

The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body. This machine creates pictures that look like slices of the knee. The pictures show the anatomy, and any injuries, very clearly. This test does not require any needles or special dye and is painless.

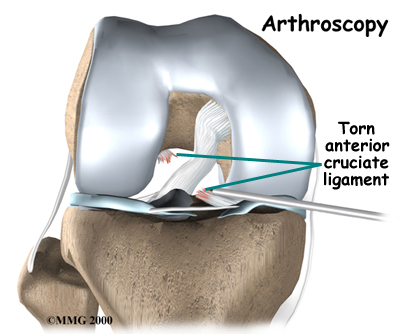

In some cases, arthroscopy may be used to make the definitive diagnosis if there is a question about what is causing your knee problem.

Arthroscopy is an operation that involves inserting a small fiber-optic TV camera into the knee joint, allowing the orthopedic surgeon to look at the structures inside the joint directly.

The vast majority of ACL tears are diagnosed without resorting to this type of surgery, though arthroscopy is used when electing to proceed with surgical repair of a torn ACL.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Initial treatment for an ACL injury focuses on decreasing pain and swelling in the knee. Rest and mild pain medications, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), can help decrease these symptoms.

You may need to use crutches until you can walk without a limp. Most patients are instructed to try and walk normally. The knee joint may need to be drained with a needle (mentioned earlier) to remove any blood in the joint.

Most patients receive physical therapy after having an ACL injury. Therapists treat swelling and pain with the use of ice, electrical stimulation, and rest periods with your leg supported in elevation. Preoperative physical therapy is one of the most important factors in preventing injury to the ACL after it has been reconstructed.

Exercises are used to help you regain normal movement of joints and muscles. Range-of-motion exercises should be started right away with the goal of helping you swiftly regain full movement in your knee.

This includes the use of a stationary bike, gentle stretching, and careful pressure applied to the knee by the therapist. Exercises are also given to improve the strength of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles. As your symptoms ease and your strength improve, you will be guided in specialized exercises to improve knee stability.

An ACL brace may be suggested. This type of brace is usually custom-made and not the type you can buy at the drugstore. It is designed to improve knee stability when the ACL doesn’t function properly. An ACL brace is often recommended when the knee is unstable and surgery is not planned.

As mentioned, a torn ACL that isn’t corrected often leads to early knee arthritis. In addition, there is no evidence that an ACL brace will prevent further damage to the knee if it is not reconstructed. The ACL brace may help keep the knee from giving way during moderate activity.

However, it can give a false sense of security and won’t always protect the knee during sports that require heavy cutting, jumping, or pivoting. Many orthopedists will also recommend wearing a brace for at least one year after surgical reconstruction, so even if you decide to have ACL surgery, a brace may be an option after surgery. Many of our high-level athletes will request a brace for a short time as they are transitioning back into their sport.

Surgery

The main goal of surgery is to keep the tibia from moving too far forward under the femur bone and to also control the increased rotation seen with an ACL deficient knee. Also, if you want to return to cutting athletics, reconstructing your ACL with significantly decrease your risk of further damaging your articular cartilage and meniscus.

Even when surgery is needed, most surgeons will have their patients attend physical therapy for several visits before the surgery. This is done to reduce swelling and to make sure you can straighten and bend your knee completely.

It is very important to obtain full knee motion prior to surgery. This practice also reduces the chances of scarring inside the joint and can speed recovery after surgery.

Arthroscopic Method

Most surgeons now favor reconstruction of the ACL using a piece of tendon or ligament to replace the torn ACL. This surgery is most often done with the aid of the arthroscope. Incisions are usually still required around the knee, but the surgery doesn’t require the surgeon to open the joint.

The arthroscope is used to view the inside of the knee joint as the surgeon performs the work. ACL surgeries are done on an outpatient basis, and patients go home the same day as the surgery. Patients with multiple ligaments that are reconstructed during surgery may stay one or two nights in the hospital if necessary.

Patellar Tendon Graft

One type of graft used to replace the torn ACL is the patellar tendon. This tendon connects the kneecap (patella) to the tibia. Dr. Kiritsis removes a strip from the center of the ligament with bone attached to each end and uses this graft as a replacement for the torn ACL.

Hamstring Tendon Graft

Dr. Kiritsis also commonly uses a hamstring graft to reconstruct a torn ACL. This graft is taken from the hamstring tendons that attach to the tibia just below the knee joint.

The hamstring muscles run down the back of the thigh. Their tendons cross the knee joint and connect on each side of the tibia. The graft used in ACL reconstruction is taken from the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons along the inside portion of the knee.

Allograft Reconstruction

Other materials are also used to replace the torn ACL. In some cases, an allograft is used. An allograft is a tissue that comes from someone else. This tissue is harvested from tissue and organ donors at the time of death and sent to a tissue bank.

The tissue is checked for any type of infection, sterilized, and stored in a freezer. When needed, the tissue is ordered by the Dr. Kiritsis and used to replace the torn ACL.

The allograft (your surgeon’s choice of graft) can be from the tibialis tendon, patellar tendon, hamstring tendon, or Achilles tendon (the tendon that connects the calf muscles to the heel).

Many surgeons use patellar tendon allograft tissue because the tendon comes with the original bone still attached on each end of the graft (from the patella and from the tibia). This makes it easier to fix the allograft in place.

The advantage of using an allograft is that Dr. Kiritsis does not have to disturb or remove any of the normal tissue from your knee to use as a graft.

The operation also usually takes less time because the graft does not need to be harvested from your knee. However, several studies have shown higher failure rates of allograft tissue as compared to using your own tissue.

Dr. Kiritsis will use allograft in only certain situations. These include revision ACL reconstructions, multi-ligament knee injuries, and patients that have lower athletic demands.

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical rehabilitation for a torn ACL will typically last six to eight weeks. Therapists apply treatments such as electrical stimulation and ice to reduce pain and swelling.

Exercises to improve knee range of motion and strength are added gradually. If your doctor prescribes a brace, your therapist will work with you to obtain and use the brace.

You can return to your sporting activities when your quadriceps and hamstring muscles are back to nearly their full strength and control, you are not having swelling that comes and goes, and you aren’t having problems with the knee giving way.

It is important to understand that patients with ACL-deficient knees that return to cutting athletics have a significant chance of causing further damage to their knees.

After Surgery

Patients will take part in formal physical therapy after ACL reconstruction. You will probably be involved in a progressive rehabilitation program for four to six months after surgery to ensure the best result from your ACL reconstruction.

At first, expect to see the physical therapist two to three times a week. If your surgery and rehabilitation go as planned during the first six weeks, you may only need to do a home program and see your therapist every few weeks over the four to six-month period.

You will be required to complete a return to athletics evaluation to be sure you are able to safely return to your sport.

Paul G. Kiritsis, MD

Dr. Kiritsis, a Richmond native, is one of a select number of Orthopedic Surgeons in the Richmond area to hold a second subspecialty board certification in Sports Medicine.